|

FOOD PSYCHOLOGY Daniel Roberts, Ph.D. & Brenda MacDonald, M.Ed. |

||

|

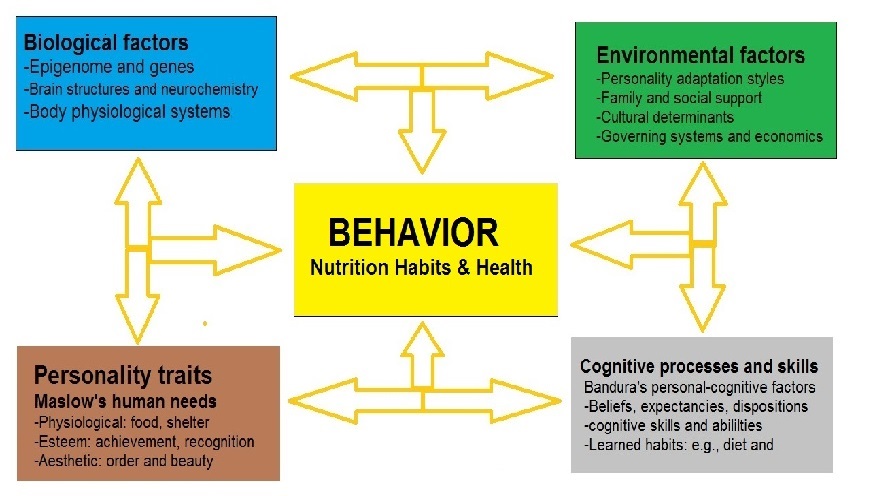

Personality and Dietary Choices Summary. Like knowledge structures (e.g., schemas and representations), personality structures influence people's thoughts, decisions, and behavior, including our dietary choices. A growing number of studies have associated health and dietary habits with personality traits such as those of the five-factor theory of personality. For instance, healthy dietary habits are associated with high levels of agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and openness/intellect, which predict better health and higher self-ratings for health. On the other hand, high scores on neuroticism and psychoticism are associated with unhealthy diets and poorer health. Other personality traits (e.g., honesty-humility and excellence-ordinariness) are considered for inclusion. The former, honesty-humility, is associated with a strong work ethic. Individuals' dietary habits have been shown to differ not just according to global traits but also according to central traits, as well as culture. Personality trait theory has the support of a number of disciplines, including behavioral genetics and neurological studies. The genetic contribution to personality traits is about 50 percent, while the other half is attributed to the environment. As such, individual's traits are malleable and subject to change. A model that encompasses several factors influencing our behavior, including our nutritional habits and health habits, is based on biological factors that are intertwined with personality and basic human needs as well as an individual's unique environmental and personal-cognitive skills.

Early personality theories conducted under the psychodynamic, behavioral, social-cognitive and humanist perspectives all contributed to much of our current knowledge about personality. More recently, personality theorists have focused on global personality traits. Personality is defined as a pattern of enduring distinctive thoughts, emotions, and behavior that characterize the way individuals adapt to their environment. Traits such as being honest, dependable, moody, impulsive, suspicious, anxious, excitable, domineering, or friendly are enduring characteristics that lead to personal and social dispositions that influence behavior across many situations. The five factor personality model Personality trait theories have evolved since Gordon Allport's Values Test (1931), Cattell's 16 Personality Factors (PF) (1949), or Eysenck's Personality Inventory (EPI) (1964). In 1987, McCrae and Costa's trait theory is an extension of previous personality theories. Based on factor analysis and multiple linear regression, McCrae and Costa's Five Factor Model, a trait-based theory of personality derived from the findings that personality can be described using five major dimensions; i.e., Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism. Openness to experience vs. Resistance. The openness factor contrasts individuals who are open to emotions, imaginative, curious, and broad-minded with those who are more traditional, concrete-minded and practical, and whose interests are more narrow (King et al., 1996). Openness is correlated with higher measures of well-being. Openness also predicts political orientations. Staerklé (2015) reported that people high in openness are more likely to endorse liberalism and express their political beliefs. \ Conscientiousness vs. Impulsiveness. This factor differentiates individuals who are self-disciplined, dependable, responsible, thorough and persevering from those who are disorganized, impulsive, careless, and who fear failure. Low conscientiousness is associated with lack of discipline and a tendency to procrastinate. Conscientiousness correlates with greater honesty, interpersonal sensitivity, inquisitiveness, and high job performance ratings (Barrick, Mount & Judge, 2001; Chamorro-Premuzic & Furnham, 2002, Judge, Heller & Mount, 2002). Extraversion vs. Introversion. This dimension contrasts traits such as being sociable, outgoing, talkative, assertive, persuasive and active with more introverted traits such as being withdrawn, quiet, passive, retiring, and reserved. Studies on the extraversion-introversion dimension has given rise to a multitude of individual differences in terms of study habits and learning styles, nutrition and work habits, circadian rhythms and musical preferences (Dai & Feldhussen, 1999; Gardner-O'Neale & Harrison, 2013; Shehni & Khezrab, 2020; Schmidt, 2016). Agreeableness vs. Antagonism. This factor is composed of a collection of traits that range from compassion to antagonism toward others. A person high on agreeableness is a pleasant person, good-natured, sympathetic, and cooperative, whereas someone low on agreeableness tends to be sceptical, unfriendly, argumentative, and even hostile. People scoring high on the agreeableness scale are also altruistic, selfless and thoughtful, always prioritizing the well-being of others. Like conscientiousness, agreeableness is predictive of job and academic performance (Witt et al., 2002). Neuroticism (negative emotionality) vs. emotional stability. People high in neuroticism are prone to emotional instability. They tend to experience more negative emotions and be moody, irritable, nervous and worried. Neuroticism differentiates people who are anxious, excitable, and easily distressed from those who are emotionally stable and thus calm, even-tempered, easygoing, and relaxed. Neuroticism is a strong correlate and predictor of different mental and physical disorders (Gale, Hagenaars, Davies et al., 2016; Lahey, 2009). Neuroticism predicts a host of lifestyle-related behavior, such as nutritional habits, health, and longevity, as well as work ethics, and relationships. For instance, neuroticism is a negative predictor of work attainment and long-lasting marriages (Roberts, Caspi, & Moffit, 2003). Figure 1: The five-factors and other possible dimensions: The five-factor model is a descriptive taxonomy where traits are hierarchically organized. At the highest level are the main factors that are linked to central traits. Central traits are clusters of traits that capture the essence of a person (e.g., honesty, intelligence, dependability); these serve as the basic building blocks of a person's personality. At the lower end of the hierarchy are secondary traits; these can be observed when a person is under the influence of a given situation.

Most studies examining the five personality factors have used a personality measure called the NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI), which was developed by Costa and McCrae (1997), and has been recently revised (NEO-PI-R). The NEO-PI provides scores on each of the facets as well as the corresponding five major factors. The more-specific dimensions allow for more accurate behavioral predictions. Interestingly, not only does the NEO-PI describe the basic structure of personality, it can also predict everyday behavior and outcome on the basis of a person's traits. For instance, people who score high on conscientiousness tend to be safe drivers (Arthur & Doverspike, 2001). Expanding the five personality dimensions Research extensively supports the five-factor theory of personality; however, some variations of this model have been proposed. One of the most prominent was developed by Michael Ashton (Ashton, 2007; Ashton & Lee, 2005; Lee et al., 2010). Ashton argues for the existence of a sixth factor: Honesty-Humility, which has been shown to be consistent across various cultures. Other personality theorists (Almagor, Tellegen & Waller, 1995; Benet & Waller, 1995; Saucier, 2009; Strus & Cieciuch, 2017; Zhou, Saucier, Gao & Liu, 2009) have found the five-personality factors restrictive and have argued that two more global traits be added; e.g., Excellence vs. Ordinariness and the Dark Triad vs. the Light Triad. Still, another personality dimension has emerged, that of liberal ideologies (Carney et al., 2008; Hirsh et al., 2010; Moss & O'Connors, 2020; Verhulst, Hatemi & Martin, 2010). Honesty-Humility. According to Ashton's Model of Personality structure (Ashton and Lee, 2007; Ashton et al., 2014). Honesty-Humility is one of the six basic personality traits. People with higher levels of honesty and humility are sincere, genuine, cooperative, fair and modest, while people with lower levels are deceitful and conceited, manipulative, greedy, and concerned with obtaining personal wealth and status. The Honesty-Humility dimension is highly correlated with agreeableness. It is negatively associated with Social Dominance Orientation (SDO) as well as with Authoritarianism. In addition, recent research has shown that the Honesty-Humility factor has a negative relationship with the 'Dark Triad' personality traits. Levels of honesty and humility predict work outcomes (e.g., job performance and workplace delinquency), creativity and risk-taking behavior, and several other personality traits related to social and life outcomes that are not accounted for by the five-factor questionnaire (Ashton, 2007; Shen, Rowatt & Petrini, 2011). Excellence vs. Ordinariness. The excellence-ordinariness factor is associated with people's natural inclination to evaluate and critique what is good or bad; e.g., talents, artistic production, and technological advances. A series of verbs and adjectives is used for that purpose; e.g., like-dislike, love-hate, trust-distrust, right-wrong, better-worse, beautiful-ugly, extraordinary-ordinary, worthy-unworthy, competent-incompetent, genuine-fake. In line with these 'descriptors', the factor 'excellence and ordinariness' has been linked to an array of variables in the realm of literary criticism, and social criticism appearing in the media (arts, music) and academia (Das, 2007; Finnis, 2011; Hochstrasser, 2004). People's natural inclination to evaluate has been shown to translate into learning, leading not only to greater insight, improvements, social recognition, competition, and innovation that secure prosperity, but also leading to social standards and institutions that reward people's accomplishments. For instance, workers are hired on the basis of their education and professional experience, athletes' performance at the Olympics will culminate in Gold, Silver or Bronze medals. And, Nobel prizes are given to individuals for their outstanding scientific contributions and intellectual achievements. Liberal ideologists vs. Authoritarian personalities. Another line of research by sociologists and social psychologists has described the Authoritarian personality (Duckitt, 2015; Oesterreich, 2005; Stone et al., 1993). At the opposite end of the authoritarian personality is liberalism. Other theories of political leadership and government (e.g., conservatism, socialism and other from the right-left political spectrum) can be traced from antiquity to the present time (Akherby, 2005; Backes, 2009, Fung, 2010; Fung, Li & Osborne,2017; Locke, 1947). Liberal ideologists are more flexible in their moral judgement, and accepting of others' beliefs and values; they respect one's freedom to speak, and regard all people as equal. On the other hand, people who have espoused authoritarian ideologies are described as more dominant, conventional in their mode of thinking, adhering to authority to whom they show absolute respect and strict obedience. The authoritarian personality correlates with social dominance, neuroticism and extraversion. The trait of liberalism is associated with openness. The Light Triad vs. Dark Triad. The Dark Triad has three factors—narcissism, psychopathy, and machiavellianism—which are commonly associated with the more antagonistic and self-interested side of human nature. The dark triad is positively correlated with low life satisfaction, as well as a range of maladaptive or aversive psycho-social-outcomes, including negative creativity, aggression and violence, and low empathy (Jones & Paulhus, 2010, 2011; Paulhus & Williams, 2002). The light triad has three factors as well: Kantianism (treating individuals with respect), Humanism (valuing the dignity and worth of each individual), Faith in Humanity (believing in the fundamental goodness of human nature) (Kaufman, 2020; Kaufman et al., 2019). The light triad includes traits such as kind-heartedness, empathy, compassion and altruism. People who are on the light side are intellectually curious, tolerant of other perspectives, agreeable in nature, and are secure in their social attachments. The light triad is positively correlated with measures of good work ethics and life satisfaction (Chamorro-Premuzic, 2017). Personality-related dietary choices A growing number of studies have reported that healthy dietary habits are associated with high levels of agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and openness/intellect, which predict self-rated good health. For instance, the trait conscientiousness is associated with health-promoting behavior and also with pro-social behavior that includes avoiding alcohol-related harm, binge drinking, and smoking. Interestingly, people who score high on conscientiousness have been found to be more sexually faithful to their spouses (Buss, 1996), and living longer than those who score low on that trait (Friedman et al., 1995; Lunn et al., 2013). On the other hand, individuals with high scores on neuroticism are associated with unhealthy diets; for instance, low consumption of fruit and vegetables, increased consumption of sugar, meat, and saturated fat (Esposito, Ceresa & Buoli, 2021; Keller & Siegrist, 2015; Pfeifer & Egloff, 2020). Individuals on such diets have poorer health and elevated mortality (Otonari et al., 2011; Reshadat et al., 2017; Wilson et al., 2004). As well, narcissism, much like psychopathy, is commonly associated with a variety of food-related disorders, including mood disorders like anxiety and depression, substance abuse, and eating disorders like bulimia and anorexia. As for extraversion and introversion, high scores on the trait of extraversion are also positively correlated with unhealthy habits and negatively correlated with dietary knowledge (Kikuchi & Watanabe, 2000). However, other studies suggest that traits associated with greater intellect, curiosity, and social engagement (e.g., openness and extraversion), are associated with greater plant-food consumption (de Bruijn et al., 2005; Conner et al., 2017). In addition, Imai and Nakachi (1990) reported the introverted type of personality was associated with diets and a life style that increases the risk of heart disease. More precisely, compared with the extraverted personality type, they showed less regularity in meal times, lower intake of animal protein foods (meat, fish and eggs), green and yellow vegetables, fruits, and cruciferous vegetables. On the effects of the dark triad-related personality traits on dietary choices and health, higher scores associated with machiavellianism and psychopathy as well as narcissism, were linked to a non-vegan lifestyle. High scorers on the dark-triad personality traits also tended to favour meat products (Sariyska et al., 2019). Importantly, several studies reported that individuals with higher scores on the Dark Triad demonstrated a high incidence of food disorders (Malesza & Kaczmarek, 2019). Taste and food preferences. Personality traits have shown to contribute to differences in taste perception, taste preference, and food preference (Becker, 1988). More particularly, preferences for a salty or sweet taste were significantly higher in groups who scored high on neuroticism; however, groups with high scores on openness and agreeableness did not like a salty taste (Kikuchi & Watanabe, 2000). Also, people high on conscientiousness avoided sweet and savory foods (Keller & Siegrist, 2015). Bitter or sour taste preferences were positively associated with aggressive cognition and antisocial personality traits (Batra, Ghoshal & Raghunathan, 2017; Ji et al., 2013; Sagioglou & Greitemeyer, 2015). Alexithymia (a personality construct characterized by the inability to identify, describe, and work with one's feelings) was associated with bitter taste responses to the bitter genetic task-marker propylthiouracil (PROP) (Robino et al., 2016). As for spicy foods, Wen et al. (2021) reported a higher frequency and stronger pungency for spicy food which was positively correlated with a preference for a salty taste such as eating snacks/deep-friend foods, drinking tea/alcohol and smoking tobacco. A Chinese study (Ma et al., 2018) reported results showing that compared with high-income residents, low-income residents preferred spicy foods. In addition, an increase in the consumption of spicy food was associated with some risk factors for cardiovascular disease (Yu et al., 2018). Overall, personality traits are characterized by distinguishable dietary habits and lifestyle. A high sugar diet or a diet high in fat and meat products are associated with specific personality traits. Healthy diets are correlated with the personality traits of conscientiousness and agreeableness, with less healthy diets being correlated with: neuroticism, and extraversion that characterizes Type A personality. Moreover, the trait excellence is associated with healthy diets, while high scorers on the dark triad are linked with unhealthy dietary habits, and high rate of disease and mortality. Personality traits were also associated with food preferences, which were in turn associated with food consumption, and healthy and unhealthy lifestyles. Some individuals savor spicy foods, while others avoid them. More individuals like salty and sweet tastes, while others are prevented from consuming sweet foods. Importantly, taste preferences lead people to consume foods that are beneficial or detrimental to their health. The reasons underlying this range of hedonic responses are varied. Some findings suggest that prior experience is a contributing factor to taste preference and food consumption, as are cultural attributes, and social and economic variables, as well as a range of genetic, physiological, and metabolic variables. Research that supports the five-factor theory Personality trait theory has the support of a number of disciplines, including behavioral genetics, neurological, and cross-cultural-studies. Personality trait theory is most amenable to research as it explores how evolution and heredity, biological, cognitive and environmental factors shape personality, and how personality dispositions affect behavior and well-being. Interestingly, mathematical algorithms (AI/ML) have led to more accurate models of how personality dispositions predict behavior and well-being. Genetic theories. Behavioral genetics provide compelling evidence for the importance of biological factors in personality. Genetic influences on personality traits have looked at correlations between the traits of identical twins (Monozygotic) who have the same genes, and fraternal twins (Dizygotic) who, on average, share only half of their genes. The evidence has been generally consistent; for example, in one review of studies involving over 24 000 twin pairs, identical twins proved markedly more similar to each other in personality than did fraternal twins (Loehlin, 1992). Tellegen et al. (1988) found identical twins raised together or apart were quite similar on several personality factors. More studies have shown that whether the trait in question is one of the five personality traits, or one of many other traits, from aggressiveness to happiness, heritability is typically around .50. This means that within a group of people, about 50 percent of the variation in such traits is attributable to genetic differences among individuals in the group (Bouchard, 1996, 2004; Jang et al., 1998; Lykken & Tellegen, 1996; Waller et al., 1990). The other half is attributed to the environment (e.g., the self development process, social status, and situational factors, including socialization and education) Neurological studies. The global trait theory is linked to neurological studies, in which people with brain damage have undergone personality change, as in the classic case of Phineas Gage. After a blasting accident that blew a steel rod through his frontal lobes, Gage showed a dramatic loss of social appropriateness (Damasio et al., 1994). This is not a surprise since Gordon Allport (1987-1967) asserted that personality traits are real entities, physically located in the brain. Allport goes on to say that each of us inherits a unique set of raw materials for given traits, which are then shaped by our experiences. Brain pathologies such as strokes, or brain tumours have revealed profound changes in personality (Feinberg, 2011). The administration of antidepressant medication and other pharmaceutical treatments, and also the overuse of recreational drugs and alcohol can change brain chemistry, or trigger personality changes, making people, for example, more extraverted and less neurotic (Bagby et al., 1999; Knutson et al., 1998). Cultural studies. The five-factor theory also has the support of studies conducted in many different languages, across different age groups, with females and males, and in various cultures (McCrae et Costa, 1990). A large-scale study that supports the five-factor theory comes from Williams, Satterwhite & Saiz (1998) who found consistent personality patterns along the five personality dimensions in 20 countries with different cultures. Even though universal personality traits are observed in many countries, cultural differences also exist among central traits underlying the major traits. Culture refers to norms, ideals, values, rules, patterns of communication, and beliefs adopted by groups and organizations. Culture is significant for many psychological phenomenon because it shapes how people raise their offspring, the values they teach, and what society and life should be like. For instance, in individualistic cultures, the independence of the individual takes precedence over the needs of the group, and the self is most often defined as a collection of personality traits (e.g., I am outgoing and ambitious) or in occupational terms (e.g., I am a high school teacher). In collectivist cultures, group harmony takes precedence over the wishes of the individual, and the self is defined in the context of relationships and community. Let's point out that personality traits are stable as long as the milieu in which we live is stable. It will remain stable if it is to our liking, and provides us with personal growth or, self-actualization (Maslow, 1970). Conflicts arise when differences arise among people, from inner conflicts, couple and group differences, endemic poverty, and so on. When a person's life is in turmoil, in a changed situation, for a multitude of reasons, he/she will take the means to make personal changes or make a personality shift, to re-establish a life equilibrium. Such is often the case when a person learns an unhealthy nutritional habit has led to a recently-diagnosed chronic illness. From human needs to personality traits While social mores change with time and place, society defines the attributes expected of its people, such as personal qualities and accomplishments. When societal expectations are met, they are evaluated as being good, valuable or worthwhile. If these are not met, people's judgments are negative and sometimes subject to prejudice. These judgments, shaped throughout our evolutionary past, encoded in our genes, and reinforced by society, drive behavior and predict survival, progress and success and are an essential part of our personality and social identity. In that context, cultural values are a contributing factor to personality. For instance, western societies emphasize quality of life, beauty, attractiveness, and personal accomplishments. Individuals on an unhealthy diet, who become ill, represent a deviation from these cultural norms. As well, the work ethic and heritage of western countries require people who are conventionally productive and healthy. These value systems of western societies have led people to change or 'improve' their personality structure, so as to adjust or fit in to societal and cultural norms, against which all of us are judged, and evaluated. It is important to remember that our personality is a unique blend of several factors, including our genes, brain structures, upbringing, culture, and the environment we live in. Moreover, personality is defined as a pattern of enduring distinctive thoughts, emotions, and behaviors that characterize the way we, as individuals, adapt to the environment. In that regard, personality traits come with value judgments; for example, a creative person is someone who is imaginative and who creates new things that can have adaptive implications. Davis Buss (2005, 2019) as well as B. F. Skinner (1987) have argued that personality traits are shaped through human history, and experience stands out as an important element of personality because of its significant adaptive implications. Of importance is the fact that our personality is influenced by our genes in more or less the same proportion that environmental factors influence our personality (i.e., about 50 percent). Thus, we are not robots, but human beings: we have a will, and are most often able to make good choices. In practice, the gene-controlled-personality aspect gives us stability, while the cognitive aspect, shaped by environmental factors, gives us opportunities for growth. Our unique biology, genetic make-up, brain structures, personality, and cognitive processes are regarded as being intertwined influences and the determinant factors that influence our behavior, including our diet and nutrition habits. Change to any or several variables (e.g., genes, biology, brain structures, culture, and environment) will likely have an influence on an individual's personality traits. For instance, for many children, maladaptive perfectionism begins with harsh, perfectionist parenting. Children will grow when parents expect a lot of them but, usually, only if they are also emotionally supportive. However, parents who are demanding and critical lead children to feel that nothing he/she does is ever good enough. As adults, these children, come to realize that perfectionism is detrimental to one's well-being, and that happiness and success, in the long run, is based on seeking excellence (Enns, Cox, & Clara, 2005). In that regard, research has shown that some aspects of our personality can be changed over time. Most agree that personality can be improved. Some findings go on to suggest that even traits that are inherited can be strengthened or weakened by experience. In fact, genes are impacted by nutrition habits; studies have shown that diet has an influence on the epigenome, which then influences gene expression. For instance, diets high in folic acid and methyl-donating nutrients can alter gene expression, resulting in poorer health, and a shorter life span (Abdul et al., 2017; Jiménez-Chillarón, Diaz & Martinez, McKay & Mathers, 2011). The therapeutic process of personality change focuses on individual, unique personality traits and cognitive factors, including disposition, feelings, expectancies, perception, and cognition, such as thoughts and beliefs. Global or universal traits are stable through life; however, personal traits influenced by the social milieu or culture, as well as personal needs, are most important in making us who we are. Individual traits and abilities are most susceptible to change when faced with disapproval or when one's expectations are not fulfilled, or when facing matters of life and death, and when basic human needs fall short. Overall, this approach to personality change is partly based on social-cognitive theories which expands the behaviourist view and humanistic perspective of personality. Albert Bandura's (1989, 1997) 'reciprocal determinism' is based on a social-cognitive view of personality. Bandura points out that three components: our environment, our behavior, and our cognition, such as thought processes and beliefs, expectancies, attitudes, and dispositions, have reciprocal roles in determining our personality and behavior. One of the important variables in Bandura's model is self-efficacy (1977), the belief that people have of the their own ability to perform competently and successfully. A strong sense of self-efficacy even allows people to create the circumstances of their own lives.

Figure 2. According to this model, our behavior is related to a multitude of factors, including food choices and health, and is the product of interactions between genes and basic human needs, environmental factors and one's cognitive processes and skills that influence our thoughts and decision making processes.

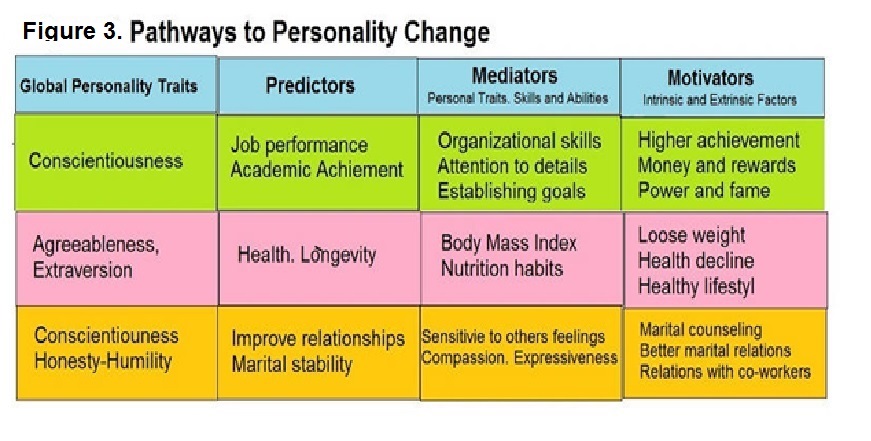

Pathway to personality change. In all, basic human needs are related to personality and predict a multitude of behavior (e.g., conscientiousness predicts job performance). An individual's personality traits are determinants of one's job performance and performance in other life domains. For instance, the skills that determine one's performance in general are organizational skills, attention to details, time management, etc. Motivation for personality change, is based on the need to expand an individual's knowledge structures and related skills and abilities associated with specific life domains (e.g., job or relationship). This leads to the creation of pathways to change some aspects of one's personality, so he/she can pave the way to a better lifestyle (see Figure 3).

References Abdul, Q.A., Yu, B.P., Chung, H.Y., Jung, H. A., & Choi, J. S. (2017). Epigenetic modifications of gene expression by lifestyle and environment. Archives of Pharmacal Research, 40(11), 1219–1237. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12272-017-0973-3 Ackerly, B. A. (I2005). Is Liberalism the Only Way toward Democracy? Confucianism and Democracy. Political Theory, 33(4), 547-576. https://doi.org/10.1177/0090591705276879 Allport, G. W., & Vernon, P. E. (1931). The Allport-Vernon Study of Values. Boston, MA. Houghton Mifflin. Almagor, M., Tellegen, A., & Waller, N. G. (1995). The Big Seven model: A cross-cultural replication and further exploration of the basic dimensions of natural language trait descriptors. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(2), 300–307. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.2.300 Arthur Jr., W., & Doverpsike, D. (2001). Prediction motor vehicle crash involvement form a personality measure and a driving knowledge test. Journal of Prevention and Intervention in the Community, 22(1), 35-42. https://doi.org/10.1080/10852350109511210 Ashton, M. C. (2007). Individual Differences and Personality. Academic Press. Ashton, M. C., & Lee, K. (2005). Honesty-Humility, the Big Five, and the Five-Factor Model. Journal of Personality, 73(5), 1321-1354. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00351.x Ashton, M. C., & Lee, K., (2007). Empirical, Theoretical, and Practical Advantages of the HEXACO Model of Personality Structure. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 11(2), 159-156. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868306294907 Ashton, M. C., Kibeom, L., & de Vries, R. E. (2014). The HEXACO Honesty-Humility, Agreeableness, and Emotionality Factors: A Review of Research and Theory. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 18(2), 139-152. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868314523838 Backes, U., (2009). Political extremes: A conceptual history from antiquity to present. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203867259 Bagby, R. M., Levitan, R. D., Kennedy, S. H., Levitt, A. J., & Joffe, R. T. (1999) Selective alteration of personality in response to nor-adrenergic compulsive disorder: Prospective long-term follow-up of 18 patients. Archives of General Psychiatry, 52(3), 384-392. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0165-1781(99)00041-4 Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Bandura, A. (1989). Social cognitive theory. In R. Vasta (Ed., Annals of child development. Six theories of child development (Vol. 6. pp 1-60). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. new York : W. H. Freeman. Barrick, M. R., , Mount, M. K., & Judge, T A, (2001). Personality and performance at the beginning for the new millennium. What do we known and where doe we go next. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 9, 9-30. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2389.00160 Batra, R. K., Goshal, T., & Raghunathan, R. (2017). You are what you eat: An empirical investigation of the relationship between spicy food and aggressive cognition. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 71, 42-48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2017.01.007 Becker, G. (1988). Accounting for tastes. Harvard University Press. Benet, V., & Waller, N. G. (1995). The Big Seven factor model of personality description: Evidence for its cross-cultural generality in a Spanish sample. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 701–718.https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.4.701 Bouchard, Jr., T. J., (1996). The genetics of personality. In K. Blum & E. P. Noble (Eds.), Handbook of Psychoneurogenetics (pp. 267-290). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. Bouchard, Jr., T. J., (2004). Genetic influence on human psychological traits: A survey. Current Direction in Psychological Science, 13(4) 148-151. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00295.x Buss, D. M. (2005). The handbook of Evolutional Psychology (Ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Buss, D. M. (2019). Evolutionary Psychology: The new Science of the Mind (6th Ed.). New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429061417 Carney, D. R., Jost, J. T., Gosling, S. D., & Potter, J. (2008). The Secret Lives of Liberals and Conservatives: Personality Profiles, Interaction Styles, and the Things They Leave Behind. Political Psychology, 29(6), 807-849. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2008.00668.x Cattell, R.B. (1949). The sixteen personality factor questionnaire, Institute for Personality and Ability Testing. Chamorro-Premuzic, T. (2017). Could Your Personality Derail Your Career? Harvard Business Review, 138-141.Chamorro-Premuzic, T., & Furnham A. (2002). Personality predicts academic performance: Evidence from two longitudinal university samples. Journal of Research in Personality, 37(4) 319-338. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(02)00578-0 Conners, T. S., Thompson, L. M., Knight, R. L. Flett, J. A. M., Richardson, A. C., & Brookie, K. L. (2017). The Role of Personality Traits in Young Adult Fruit and Vegetable Consumption. Frontiers in Psychology, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00119 (1997). Stability and Change in Personality Assessment: The Revised NEO Personality Inventory in the Year 2000. Journal of Personality Assessment, 68(1), 86-94. https://DOI:10.1207/s15327752jpa6801_7 Dai, D. Y & Feldhusen, J. F. (1999). A validation study of the thinking styles inventory: Implications for gifted education. Roeper Review, 21(4), 302-307. https://DOI:10.1080/02783199909553981 Damasio, H., Grabowsky, T., Frank, R. Galaburda, A. M., & Damasio, A. R. (1994). The Return of Phineas Gage: Clues About the Brain from the Skull of a Famous Patient. Science, 264, 1102-1105. https://doi.org/: 10.1126/science.8178168Das, B. K. (2007) Twentieth century Literary criticism (5th Ed.). Atlantic Publishers. de Bruijn, G.J., Kremers, S. P. J., van Mechelen, W., & Grug, J. (2005). Is personality related to fruit and vegetable intake and physical activity in adolescents. Health Education Research, 20(6), 635-644. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyh025 Duckitt, J., (2015). Authoritarian Personality. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences (2nd ed, pp. 255–261). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.24042-7 Enns, M. W., Cox, B. J., & Clara, I. P. (2005). Perfectionism and neuroticism: A longitudinal study of specific vulnerability and diatheses-stress models. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 29(40), 463-478. Esposito, C. M., Ceresa, A., & Buoli, M. (2021). The association between personality traits and dietary choices: A systematic review. Advances in Nutrition, 12(4), 1149-1159. https://doi.org/10.1093/advances/nmaa166 Eysenck, H. J., & Eysenck, B. G. (1964). Manual of the Eysenck Personality Inventory. Hodder and Stoughton. Feinberg, (2011). Neuropathologies of the self: Clinical and anatomical features. Consciousness and Cognition, 20(1), 75-81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2010.09.017 Fung, X., Li, W., & Osborne E. W. (2017). Classical liberalism in China: Some history and prospects. Econ Journal Watch, 14(2), 218-240. Finnis, J. (2011). Natural law and natural rights (2nd Ed.). Oxford University Press. Friedman, H. S., Tucker, J. S., Schwartz, J., Martin, L. R., et al. (1995). Childhood conscientiousness and longevity: Health behaviors and cause of death. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(4), 696-703. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.68.4.696 Fung, F. S. K. (2010). Liberalism in China and Chinese Liberal Thought. In the intellectual foundation of Chinese modernity: Cultural and Political thought in the republican era. The American Historical Review 116(2), 428-429. New York: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1086/ahr.116.2.428 Gale, C. R. Hagenaars, S. P., Davies, G., et al. (2016). Pleiotropy between neuroticism and physical and mental health: findings from 108 038 men and women in UK Biobank. Translational Psychiatry, 6, 791 https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2016.56 Gardner-O' Neale, L. D., & Harrison, S. (2013). An Investigation of the learning styles and study habits of chemistry undergraduates in Barbados and their effect as predictors of academic achievement in chemical group theory. Archives, 3(2), https://doi/DOI:10.5901/jesr.2013.v3n2p107 Hirsh, J. B., DeYoung, C. G., Xu, X., & Peterson, J. B. (2010). Compassionate liberals and polite conservatives: Associations of agreeableness with political ideology and moral values. Personality and Social Psychology Bulleting, 36(5), 655-664. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167210366854 Hochstrasser, T. J. (2004). Natural law theories in the early enlightenment. Cambridge University Press. Imai, K., & Nakachi, K. (1990). Personality and life style. Japanese Journal of Public Health, 37(8):577-584. Jang, K. L., McCrae, R. R., Angleitner, A., et al. (1998). Heritability of facet-level traits in a cross-cultural twin sample: Support for a hierarchical model of personality. Journal of personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1556-1565. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.6.1556 Ji, T., Yi, D., Huan, D., & Ma, J. Does "spicy girl" have a peppery temper? the metaphorical link between spicy tastes and anger. Social Behavior and Personality. An International Journal, 41(8), 1379-1385. https://doi/10.2224/sbp.2013.41.8.1379 Jiménez-Chillaróna, J. C., Diaz, R., Martinez, D., et al. (2012). The role of nutrition on epigenetic modifications and their implications on health. Biochimie, 94(11), 2242-2263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biochi.2012.06.012 Jones, D. N., & Paulhus, D. L. (2010). Different provocations trigger aggression narcissists and psychopaths. Social and personality psychology Science, 1, 12-18. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550609347591 Jones, D. N., & Paulhus, D. L. (2011). Differentiating the dark triad within the interpersonal circumplex. In L. M. Horowitz & Strack . S., Handbook of Interpersonal Psychology: Theory, Research, Assessment, and therapeutic interventions (pp. 249-266). John Wiley & Sons. Judge, T. A., Heller, D., & Mount, M. K. (2002). Five-factor model of personality and job satisfaction: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(3), 530–541. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.3.530 Kaufman, S. B. (2020). Transcend: The new science of self-actualization. Penguin Random House. Kaufman, S. B., & Yaden, D. B., Hyde, E., & Tsukayaman, E. (2019). The light vs. dark triad of personality: Contrasting tow very different profiles of human nature. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 467 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00467 Keller C., & Siegrist, M. (2015). Does personality influence eating styles and food choices? Direct and indirect effects. Appetite, 84(1), 128-138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2014.10.003 Kikuchi, Y., & Watanabe, S. (2000). Personality and dietary habits. Journal of Epidemiology, 10(3), 191-198. https://doi.org/10.2188/jea.10.191 King, L. A., Walker, L. M., & Broyes, S. J. (1996). Creativity and the five-factor model. Journal of Research in Personality, 30(2), 189-203. https://doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.1996.0013 Knutson,B., Wolkowitz, O. M., Cole, S. W., et al. (1998). Selective alteration of personality and social behavior by serotonergic intervention. American Journal of Psychiatry, 155(3), 373-379. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.155.3.373 Lahey, B. B. (2009). Public health significance of neuroticism. American Psychologist, 64(4), 241–256. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015309 Lee, K., Ashton, M. C., Ogunfowora, B., Bourdage, J. S. & Shin, K. H. (2010). The personality bases of socio-political attitudes: The role of Honesty–Humility and Openness to Experience, Journal of Research in Personality, 44(1), 115-119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2009.08.007Locke, John. (1947). Two Treatises of Government. New York: Hafner Press Loehlin, J. C. (1992). Genes and the environment in personality development. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Lunn, T. E., Nowson, C.A., Worsley, A., & Torres, S. I. (2014O). Does personality affect dietary intake? Nutrition, 30(4), 403-409. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2013.08.012 Lykken, D. T., & Tellegen, A. (1996). Happiness is a stochastic phenomenon. Psychological Science, 7, 186-189. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40062939 Ma, C., Song, Z., Yan, X, , S., & Zhao, G. (2018). Accounting for tastes: do low-Income populations love spicy foods more? The Journal of Chinese Sociology, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40711-018-0089-2 Malesza, M., & Kaczmarek, M.C. (2021). Dark side of health-predicting- health behaviors and diseases with the Dark Triad traits. Journal of Public Health, 29, 275–284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-019-01129-6 Maslow, A. (1970). Motivation and personality. New York: Harper & Row. McCrae, R. R., & Costa, Jr., P. T. (1987). Validation of the five-factor model of personality across instruments and observers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(1), 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.1.81 McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. Jr. (1990). Traits and trait names: How well is openness represented in natural languages. European Journal of Personality, 4, 119-129. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2410040205 McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T., Jr. (1997). Personality trait structure as a human universal. American Psychologist, 52(5), 509–516. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.52.5.509 McKay, J. A., & Mathers, J. C. (2011). Diet induced epigenetic changes and their implications for health. Acta Physiologica, 202(2), 103-118. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-1716.2011.02278.x Moss, J., & O'Connors, P. J. (2020) The Dark Triad traits predict authoritarian political correctness and alt-right attitudes. Heliyon, 6(7). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04453Oesterreich, D. (2005). Flight into security: A new approach and measures of the Authoritarian personality. Political Psychology, 26(2), 275-298. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2005.00418.x Otonari, J., Nagano, J., Morita, M., et al. (2011). Neuroticism and extraversion personality traits, health behaviours, and subjective well-being: the Fukuoka Study (Japan). Quality of Life Research 21(10), 1847–1855. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-011-0098-y Paulhus, D. L., & Williams, K. (2002). The dark triad of personality. Narcissism, Machiavellianism and psychopathy. Journal of Research in Personality, 36(6), 556-563. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(02)00505-6 Pfeifer, T. M., & Egloff, B. (2020). Personality and eating habits revisited: Associations between the big five, food choice, and Body Mass Index. Appetite, 149(1). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2020.104607 Reshadat, S., Zakiei, A., Hatamin, P., et al. (2017). A Study of the correlation of personality traits (Neuroticism and Psychoticism) and self-efficacy in weight control with unhealthy eating behaviors and attitudes. Annals of Medical & Health Science Research, 7, 32-38. Roberts, B. W., Caspi, A., & Moffitt, T. E. (2003). Work personality experience and personality development in young adults. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(3), 582–593. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.3.582 Robino, A., Mezzavilla, M., Pirastu, N., La Bianca, M., Gasparini, P., Carlino, D., & Tepper, B. J. (2016). Understanding the role of personality and alexithymia in food preferences and PROP taste perception. Physiology & Behavior, 15 (1), 72-78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.01.022 Sagioglou, C., & Greitemeyer. (2015). Individual differences in bitter taste preferences associated with antisocial personality traits. Appetite, (96)1, 299-308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2015.09.031 Sariyska, R., Markett, S., Lachmann, B., & Montag, C. (2019). What Does Our Personality Say About Our Dietary Choices? Insights on the Associations Between Dietary Habits, Primary Emotional Systems and the Dark Triad of Personality. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02591 Saucier, G. (2009). Recurrent Personality Dimensions in Inclusive Lexical Studies: Indications for a Big Six Structure. Journal of Personality, 77(5), 1577-1614. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00593.x Schmidt, S. J. (2016). Personality diversity: Extrovert and introvert temperaments. Journal of Food Science Education. 15(3), 73-74. https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-4329.12091 Shehni, M. C., & Khezrab, T. (2020). Review of literature on learners' personality in language learning: Focusing of extravert and introvert learners. Theory and Practice n language Studies, 10(11), 1478-1483. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/tpls.1011.20 Shen, M. J., Rowatt, W. C.& Petrini, L. (2011). A new trait on the market: Honesty-Humility as a unique predictor of job performance ratings. Personality and Individual Differences, 50(6), 857-862. https://doi.org/DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2011.01.011 Skinner B. F. (1987). Why we are not acting to save the world. Chapter 1. Skann til s:W1 ( 600 dpi PDF): (tvburkey.org) Staerklé, C. (2015). Political psychology. In: James D. Wright (editor-in-chief), International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, (2nd ed., Vol 18, pp. 427-433). Oxford: Elsevier.. Stone, W. F., Lederer, G., & Christie, R. (1993). Strength and weakness: The authoritarian personality Today. New York, NY: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4613-9180-7 Strus, W., & Cieciuch, J. (2017). Towards a synthesis of personality, temperament, motivation, emotion and mental health models within the Circumplex of Personality Metatraits. Journal of Research in Personality, 66, 79-95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2016.12.002Tellegen, A., Lykken, D. T., Bouchard, T. J., Wilcox, K. J., Segal, N. L., & Rich, S. (1988). Personality similarity in twins reared apart and together. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1031–1039. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022- Verhulst, B., Hatemi, P. K., & Martin, N. G. (2010). The nature of the relationship between personality traits and political attitudes. Personality and Individual Differences, 44(4), 378-379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.11.013 Waller, N. G., Kojetin, B. A., Bouchard, T. J., Jr., t al (1990). Genetic and environment influences on religious interests, attitudes, and values: A study of twins reared apart and together. Psychological Science, 1, 138-142. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40062599 Wen, Q., Wei, Y., Du, H., Lv, J., Guo, Y., Bian, Z., et al. (2021). Characteristics of spicy food consumption and its relation to lifestyle behaviours: results from 0.5 million adults. International Journal of Food Science and Nutrition, 72(4), 569-576. https://doi.org/10.1080/09637486.2020.1849038 Williams, J. E., Satterwhite, R. C. & Saiz, J. L. (1998). The importance of psychological traits: A cross-cultural study. New York: Plenum Wilson, R. S., Mendes de Leon, C. F., Bienias, J. L., Evans, D. A., & Bennett, D. A. (2004). Personality and Mortality in Old Age. The Journals of Gerontology, 59(3), 110-116. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/59.3.P110 Witt, L. A., Burke, L. A., Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. (2002). The interactive effects of conscientiousness and agreeableness on job performance, Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(1), 164-169. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.1.164 Yu, K., Xue, Y., He, T., Guan, L., Zhao, A., & Zhang, Y. (2018). Association of spicy food consumption frequency with serum lipid profiles in older people in China, The Journal of Nutrition, Heath & Aging, 22(3), 311-320. https://doi 10.1007/s12603-018-1002-z Zhou, X., Saucier, G., Gaom D., & Liu, J. (2009). The factor structure of Chinese personality terms. Journal of Personality, 77(2), 363-400. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00551.x

|