|

FOOD PSYCHOLOGY Daniel Roberts, Ph.D. & Brenda MacDonald, M.Ed. |

||||||||||||

|

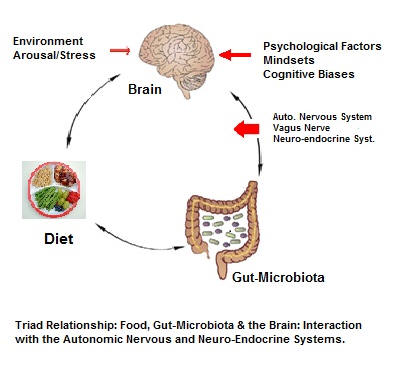

Biases relating to food and nutrition The deep breath that is associated with muscle relaxation, meditation, yoga and other calming techniques involves the vagus nerve which starts at the brain stem and winds its way through the body, coiling itself around the heart and the gut. The vagus nerve sends signals via neuropod cells that interconnect the brain and the gut microbiome. Food impacts the activity of the gut microbiome, the brain, the heart and other internal organs, that leads to changes in overt and covert behavior. Indeed, studies show that alterations in subjects' behavior profile (i.e., stress-related and affective disorders) ensue from diet-induced alterations within the microbiota-gut-brain axis (Pignotti & Steinberg, 2001; Rechlin et al., 1994, Bruijn et al, 1996, Davidson et al, 2000).

The misattribution of arousal Stress, arousal or anxiety follows activation of the sympathetic nervous system, the brain interacting with the gut and the heart via the vagus nerve. Stress is sometimes psychological, such as worrying about losing a job. Other times, the cause of anxious feelings can be environmental, such as worry about a job interview. Regardless the cause of arousal or stress, higher levels of anxiety cause the human body to react by releasing the stress hormone, cortisol, resulting in physiological changes that include a pounding heart, faster breathing, tensing of muscles and perspiration. Misattribution of arousal is a cognitive bias, whereby people make an error in assuming what is causing them to feel aroused. For example, when actually experiencing physiological responses related to fear, people have mislabelled these responses as romantic arousal. The arousal is interpreted according to the environmental context, or attributed to disease, or external threats. For instance, a young man sought a residence near a hospital after developing a fear of an oncoming heart (i.e., panic) attack following the symptoms of cannabis (marijuana) withdrawal (e.g., irritability and restlessness). The reason physiological symptoms are attributed to incorrect stimuli is because many stimuli produce similar symptoms, such as increased blood pressure, shortness of breath, and sweating. Donald Dutton and Arthur Aron's experiment (1974) tested the misattribution of the symptoms of arousal. They had an attractive female confederate wait at the end of a bridge that was either a suspension bridge (fear-inducing condition) or a sturdy bridge (non-fear-inducing). After each male crossed the bridge, he was stopped by a female confederate and given a Thematic Apperception Test: i.e., a projective personality test designed to assess the participants' responses. Afterward, the female confederate gave her phone number to the participant in case he had any questions about the experiment. It was found that males crossing the 450-foot-long suspension bridge over a river were more likely to contact the female confederate than those who crossed the shorter bridge lower to the ground. It was concluded that men found the woman more attractive when experiencing anxiety crossing the higher and longer suspension bridge. This was interpreted to mean that love involves a state of arousal. Later experiments used a shot of epinephrine to stimulate emotional arousal. Epinephrine, also called adrenaline, is a hormone produced by the adrenal medulla. A study conducted by Allen, Kenrick, Linder and McCall (1989) suggested that there are other types of arousal (e.g., cognitive, or intellectual arousal, and/or affective and emotional arousal) that can be misattributed to a target person, an object or situation. Contrary to the misattribution model, it was theorized that arousal facilitates sexual attraction even when subjects' attention was directed to the actual source of arousal. In other words, regardless of whether the person is aware of the true cause of his arousal, the male participants would still be more attracted to the target person. The question that presents itself is whether food, in association with certain situations, triggers an arousal response (e.g., during a pleasant candle-lit dinner or while getting heart burn from eating lunch on-the-run). Would this response be misattributed to covert stimuli (ruminations) or overt stimuli (music or ambient smells and/or lighting). Misattributions involving food and nutrition There are countless stories of people experiencing a surge of arousal or stress where food was associated with joy, fear, or anger, and with arousal being misattributed to either overt or covert factors. For example, a businessman at a dinner meeting has his favourite meal, which is filet mignon with rice pilaf and veggies. He has high expectations of the meeting, hoping for a business deal that would put his company ahead. Unfortunately, towards the end of his meal, our businessman experiences nausea, runs out of the restaurant, and vomits on the sidewalk. He gets very sick and spends days in bed recovering from - not food poisoning as he had thought - but stomach flu. He misattributes the cause of his illness to the filet mignon, which he stops eating altogether. A common misattribution error occurs when people report having had 'un coup de coeur' (French for being 'love struck'). A man's girlfriend, whom he had dated for five years, left him for another man. The man's friends invited him to a restaurant to celebrate New Year's Eve, hoping that a change of scenery would do him good. There was a nine-course meal, including French pastries for desert, espresso coffee, and champagne at the stroke of midnight. A lot of entertainment and chatting occurred during the celebration. Interestingly, during that time, our disillusioned man fell in love with a total stranger, who was a dietician-naturopath while he was a food purchaser for a large retailer. Even though both shared a common interest in food, 'love at first sight' was said to be the glue that cemented their union. We all have a liking for some foods and a dislike of other foods. However, it is most likely that our appreciation of food depends on a number of factors that include the environment, our brain and emotional reactions, as well as the activity of our internal organs connected to the brain via the vagus and cranial nerves. A food experience associated with emotion, such as pleasure or fear, is known to make our organs react with a series of physiological changes. These changes, stimulated by the sympathetic nervous system, include an increase in heart rate, amorous feelings, rapid breathing, increased blood flow to the muscles, and elevated blood pressure. The sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system that participates in these changes is driven by neurotransmitters, such as norepinephrine or adrenaline, a hormone released in stressful situations, or while engaging in physical activities (e.g., skydiving), or when watching an exciting suspense movie. A psychologist once reported having read in a textbook that "Learning is a stimulated interaction." This concept comes from the constructivists who also affirmed that "Learning is a meaningful interaction." This idea was extended by the concept that people seek knowledge to reduce or stop cognitive noise: an uneasy gut-brain feeling that needs to be addressed. A person's inner voice would then intervene to seek information, find a rationale, or make attempts to explain conflicting thoughts. Our psychologist recalled having been asked by a co-worker if he smoked. He said, "No," and was asked what he did to relax. After some thought, he said, "I enjoy a coffee with a Danish pastry." Little was the smoker aware that the relaxing effect attributed to smoking tobacco is due to the action of nicotine ending withdrawal symptoms in addicted smokers. Our psychologist also said that the misattribution-like process is a cognitive bias, that can, like other types of cognitive bias and distortion, pave the way for all sorts of outcomes having little to do with reality. This is often the case with food-related diseases (e.g., bulimia, anorexia, heart issues and type 2 diabetes, and liver and kidney problems). People affected by such diseases experience cognitive distortions (e.g., body dysmorphia) as well as cognitive-related biases (e.g., doomsday beliefs). There are cognitive biases related to food choice when we think in terms of Freud's defence mechanisms (e.g., rationalization: how people justify eating meat, or not eating pork). Other cognitive biases are fallacies (e.g., 'Man is a vegetarian' or 'Man is a meat-eater'). Research on biases in food-choice Ong et al., (2017) examined studies that describe how cognitive dissonance affects attitudes to food and nutrition. A quasi-experiment was reported that investigated whether individuals would continue consuming chicken wings if they believed that the chicken wings were tainted with viruses. It was found that the more chicken was consumed, the less the participants agreed that the chicken was tainted. Also, the participants made more attempts to justify their position, ignoring the risk. Heuristics has also been researched in relation to food and nutrition. Rozin et al, (1996) studies explored Americans' tendency to simplify nutritional information according to a good/bad dichotomy. It was reported that all subjects confounded nutritional completeness with long-term healthfulness of food. To account for such differences, it was suggested that the following heuristics and biases played a role: dose intensity, categorical perception, a 'monotonic mind' belief (if something is harmful at high levels then it is harmful at low levels) and the 'magical' principle of contagion. Miles and Scaife (Scaife et al., 2006) reported that food consumption patterns are influenced by a number of things, including social and cultural factors. Their focus was on individuals' tendencies to believe that they are less likely than their peers to experience negative events, and more likely to experience positive events: a phenomenon known as the 'optimistic bias'. It was argued that the optimistic bias has a negative impact on both self-protective behaviour and on efforts to promote risk-reducing behaviours, resulting in individuals eating unhealthy food as opposed to healthy food. Magical thinking has been regarded as a cognitive distortion whereby individuals invoke mystical beliefs to cope with stressful situations as well as to account for personal food choice or the adoption of a specific diet. James et al. (2011) reported that individuals attempting to lose weight adopt food practices imbued with magical thinking in the form of creative persuasion, retribution (giving self rewards or punishment), and efficient causality (a specific food or diet, medicine or activity being associated with a lower or higher risk of chronic disease). In summary, food consumption or dietary preference is affected by an individual's mindset, as well as cognitive biases. As the saying goes: "There is no reality but self-perception". Most often, our perception of food guides our consumption and diet preference. It is worthy to note that an individual's perception of food is also impacted by activity levels of the internal organs, the gut-microbiota interaction, and the brain connections with organs that are regulated by the autonomic nervous system and neuro-endocrine system (e.g., enzymes and hormones from the pancreas, such as insulin that regulates glucose level, and the adrenal glands' secretion of epinephrine and norepinephrine). It is the interaction of these factors, among others, that influences an individual's thought processes, food choice or diet, eating habits, and health.

References Allen, J. B., Kenrick, D. T., Linder, D. E., & McCall, M. A. (1989). Arousal and attraction: A response-facilitation alternative to misattribution and negative-reinforcement models. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(2), 261–270. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.2.261 Davidson, R. J., Marshall, J. R., Tomarken, A. J., & Henriques, J. B. (2000). While a phobic waits: regional brain electrical and autonomic activity in social phobics during anticipation of public speaking. Biological Psychiatry (47)2, 85-95. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3223(99)00222-X Dutton, D. G., & Aron, A. P. (1974). Some evidence for heightened sexual attraction under conditions of high anxiety. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 30(4), 510–517.https://doi.org/10.1037/h0037031 Gomez, P. (2012). Common biases and heuristics in nutritional quality judgments: a qualitative exploration. International Journal of Consumer Studies (37), 2, 152-158. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-6431.2012.01098.x Kaelberer M. M., Rupprecht, L. E., Liu, W. W., Weng, P., & Bohórquez, D. V. (2020). Neuropod cells: The emerging biology of gut brain sensory transduction. Annual Review of Neuroscience (43), 337-353. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-neuro-091619-022657 Liddle, R. A. (2019). Neuropods. Cellular and molecular gastroenterology and hepatology, 7(4), 739-747. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmgh.2019.01.006 Ong, A. S.-J., Frewer, L., & Chan, M.-Y. (2017). Cognitive dissonance in food and nutrition – A Review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition (57), 11. 2330-2342. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2015.1013622 Pignotti, M., & Steinberg, M. (2001). Heart rate variability as an outcome measure for Thought Field Therapy in clinical practice. Journal of Clinical Psychology 57(10), 1193-1206. Scaife, V., Miles, S., & Harris, P. (2006). The impact of optimistic bias on dietary behaviour. In R. Shepherd & M. Raats (Eds), The psychology of food choice (pp.311-399). Guildford Press. St. James, Y., Handelman, J. M., & Taylor, S. F. (2011). Magical Thinking and Consumer Coping. Journal of Consumer Research (38) 4, 632–649. https://doi.org/10.1086/660163

|

||||||||||||